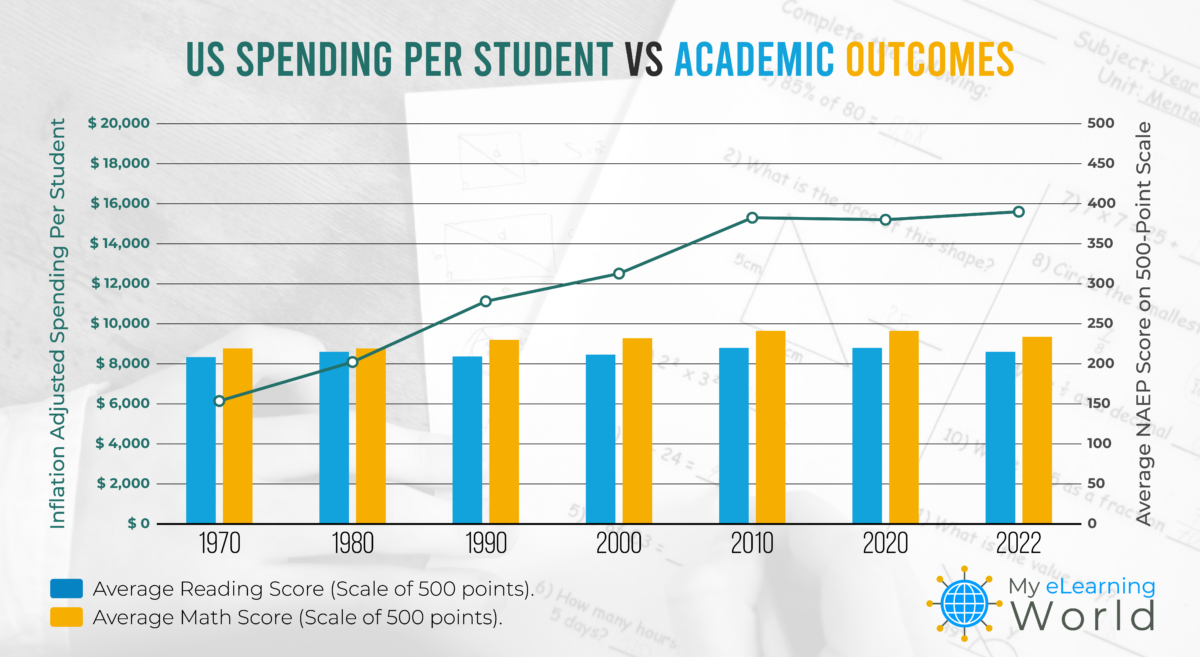

For decades, taxpayer spending on K-12 education has consistently increased, outpacing inflation by 2.5 times over the past 50 years. But while most people believe that more funding should lead to better outcomes for students, the evidence indicates that higher spending alone has had little impact on improving student achievement.

We did a comprehensive study examining half a century of educational spending and academic outcomes in the United States, and we found a concerning trend — despite significant increases in funding, improvements in student performance have been minimal.

Since 1970, the U.S. has ramped up its educational spending by an astounding 154%, adjusted for inflation. This investment aimed to bolster student achievements in critical areas such as reading and mathematics. Yet, the outcomes have been underwhelming. Reading scores have nudged up by just 3%, and math scores have seen a slightly better improvement at 7%.

| Year | Raw Spending Per Student | Inflation-Adjusted Spending Per Student | Average Reading Score (Scale of 500 points) | Average Math Score (Scale of 500 points) |

| 1970 | $816 | $6,155 | 208 | 219 |

| 1980 | $2,272 | $8,069 | 215 | 219 |

| 1990 | $4,980 | $11,151 | 209 | 230 |

| 2000 | $7,394 | $12,566 | 212 | 232 |

| 2010 | $11,433 | $15,344 | 220 | 241 |

| 2020 | $13,501 | $15,266 | 220 | 241 |

| 2022 | $15,633 | $15,633 | 215 | 234 |

When you compare US educational outcomes to other developed countries, things become even more concerning.

American students typically perform at a middling level compared to their global counterparts, especially in subjects such as mathematics.

Deeper analysis shows American millennials also rank last in problem-solving among counterparts from other industrialized nations.

This places the US at a competitive disadvantage, highlighting a gap between spending and actual skill development in the workforce.

The Great Recession and the recent COVID-19 pandemic have further complicated the educational landscape.

Despite the rebound in spending post-recession, the pandemic pushed national reading and math scores to their lowest in decades.

So how is it that we’re spending more than ever on education but not seeing significant improvements in academic outcomes? Some argue that the allocation of the funds is the problem.

Since 2000, there has been a 95% growth in administrative staff at public schools. During that same time, there’s only been a 5% increase in students.

In other words, a significant portion of the increased funding is going towards expanding administrative roles rather than directly enhancing classroom instruction or resources.

This disparity suggests that while schools are receiving more money, much of it is not being utilized in ways that directly impact student learning, potentially contributing to the stagnation in academic outcomes.

As the debate over educational funding in the US continues, this study shows that just increasing budgets isn’t enough. The focus needs to shift toward how those resources are actually being used. Unless the approach to education spending is seriously rethought, it seems likely that taxpayers will continue to get an underwhelming return on their investment.

- Elevating Your Virtual Presence: Why EMEET’s SmartCam S800 Stands Out in Modern Communication - 06/04/2025

- US Teachers Will Spend $3.35 Billion of Their Own Money on Classroom Expenses in 2025-25 School Year - 06/04/2025

- Report: Leveraging AI Tools Could Help US Teachers Avoid $43.4 Billion of Unpaid Overtime Work - 06/04/2025